Smilax

|

Family: Smilacaceae |

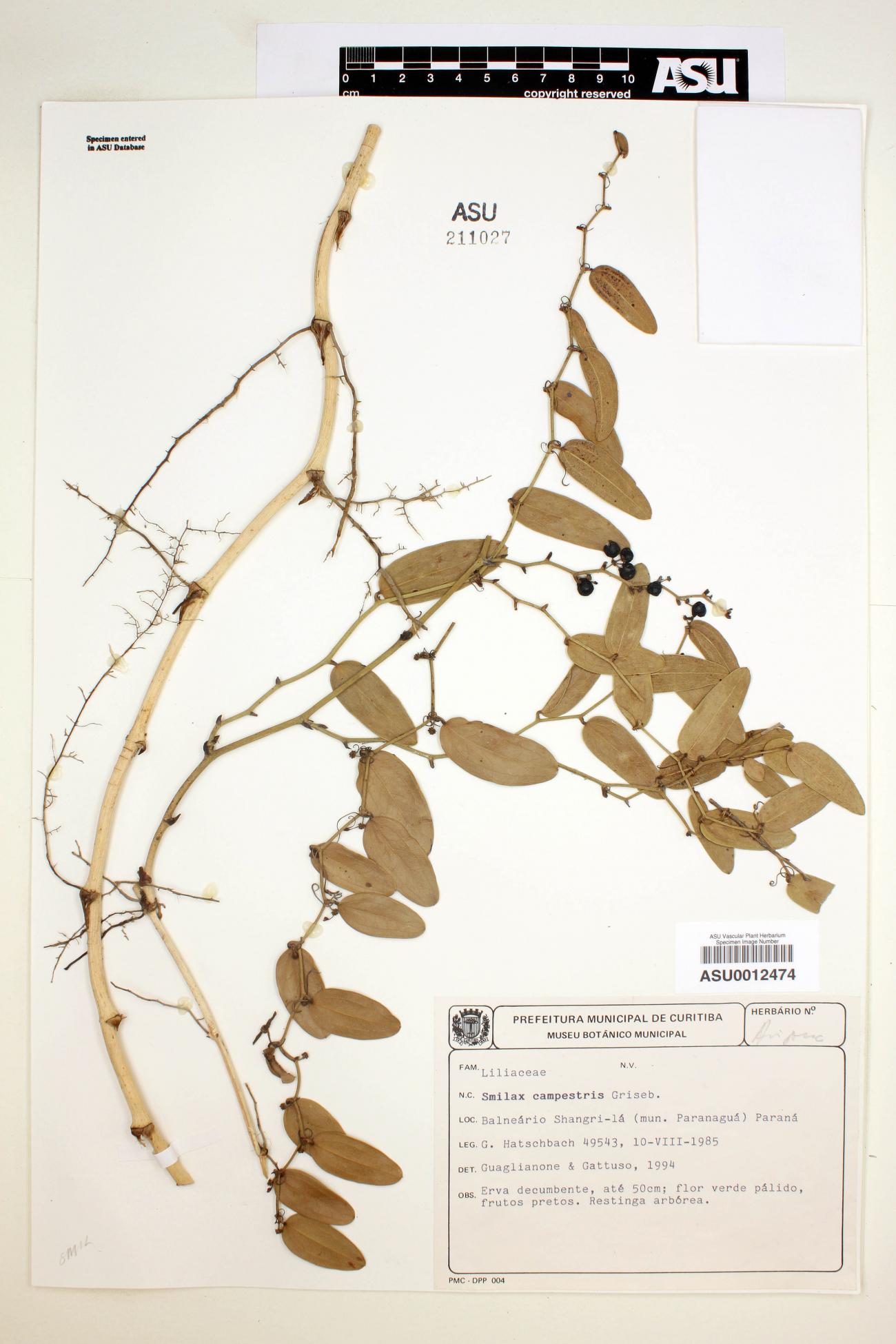

Shrubs, vines, or herbs; rhizomes tuberous or stoloniferous, woody; roots filiform. Stems erect, sprawling or, more often, climbing, simple or branching, unarmed or armed with prickles; woody or herbaceous. Leaves deciduous or evergreen, alternate; stipules present; tendrils often present (few or rudimentary in S. hugeri and S. ecirrhata, absent in S. biltmoreana), paired, originating from petioles; blade linear, oblong, ovate, or, sometimes, reduced to scales in herbaceous species, base sometimes lobed. Inflorescences umbellate, axillary to leaves or bracts, loose to dense, pedunculate. Flowers unisexual; tepals 6, greenish, yellow, or bronze, ovate to elliptic; staminate flowers sometimes with pistillode, stamens 6, anthers basifixed, dehiscence introrse; pistillate flowers with 6 staminodes, style short or absent, stigmas 3, recurved, ligulate. Berries black, blue, purple, red, or orange. x = 13-16. The North American herbaceous species of Smilax (numbers 2, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, and 15 in this treatment) traditionally have been placed in sect. Nemexia (Rafinesque) A. de Candolle. J. K. Mangaly (1968) concluded that the correct name for this group at that rank is sect. Coprosmanthus (Torrey) Bentham. The remaining North American species, all more or less woody, belong to sect. Smilax. The relatively small number of species (20) present in the flora does not warrant the elaboration of an updated subgeneric classification, which should take into account all species of the genus on a worldwide basis. The leaves of Smilax are very unusual. A. Arber (1918, 1920) believed that the 'blade of Smilax is not equivalent to the lamina of a dicotyledon but is merely a `pseudolamina´ representing an expansion of the upper region of the petiole.' In this view, tendrils are also proliferations of the petiole and are not homologous to tendrils of dicotyledons. However, D. R. Kaplan (1973) remarked that unifacial monocotyledonous leaves never exhibit a lamina rudiment at the apex, and therefore there is no convincing argument that their apices are simply petiolar. He suggested that the terete leaf axis of monocotyledons is not merely an expanded petiole but is positionally equivalent to the lamina region of a dicotyledonous leaf. Smilax leaves lack an abscission layer, but the distal portion of the petiole undergoes a soft disintegration and the 'blade' falls, leaving a rough end on the stub (W. C. Coker 1944). Smilax has numerous uses. Sarsaparilla, a beverage and medicinal used against rheumatism, is obtained from the rhizomes of various species, mainly from Mexico and Central America. A jelly can be made from the rhizomes. The fleshy rhizomes of several vining species, most notably S. smallii, which have a texture of firm, crisp apples, were used by Native Americans and early settlers in the same manner as were potatoes, or else in making bread or mush. The young, succulent stems of several species are cooked and used as asparagus or the tender stems may be used in salads. Seeds were sometimes used as beads ('Indian coral') and a brown dye can be made from the roots of various species. Woody rhizomes were reportedly used by Native Americans and settlers in making pipes. Some species have been used in Native American (D. E. Moerman 1986) and folk medicine. All species of Smilax are excellent wildlife food and are also browsed, or the rhizomes dug and eaten, by domestic stock.

Dioecious; fls in axillary pedunculate umbels, rather small, the staminate often a little larger than the pistillate; tep spreading, greenish or yellowish; filaments borne at the base of the tep; anthers basifixed; style none or very short; stigmas solitary or 3, oblong, recurved; ovules orthotropous, 1 or 2 per carpel. 300, cosmop. Gleason, Henry A. & Cronquist, Arthur J. 1991. Manual of vascular plants of northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. lxxv + 910 pp. ©The New York Botanical Garden. All rights reserved. Used by permission. |