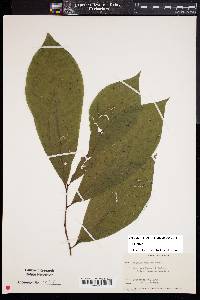

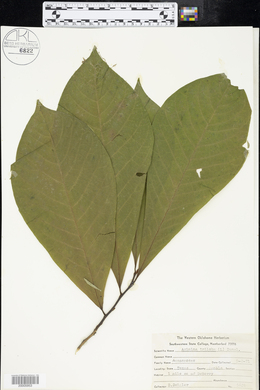

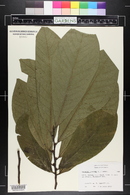

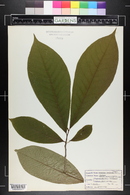

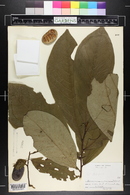

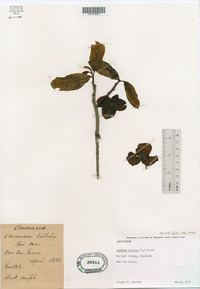

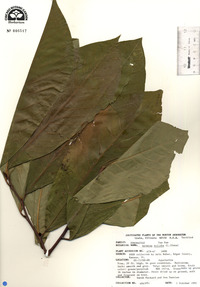

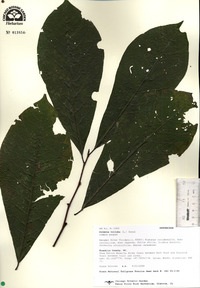

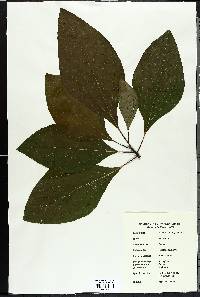

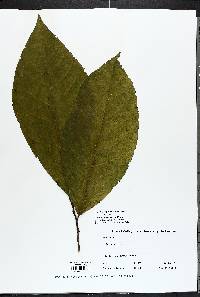

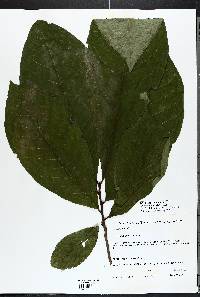

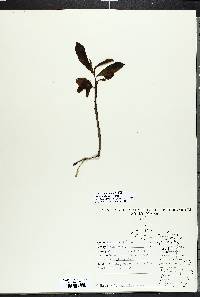

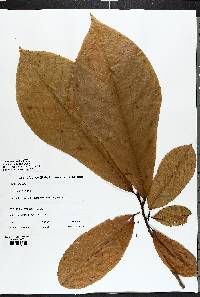

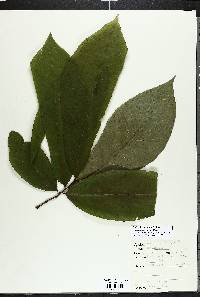

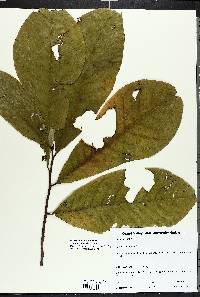

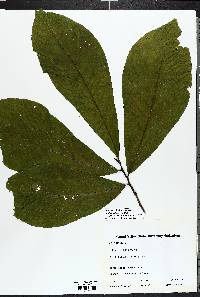

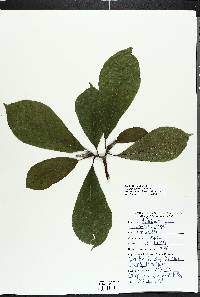

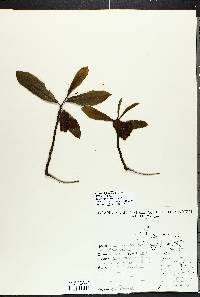

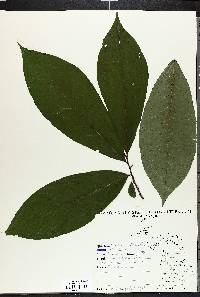

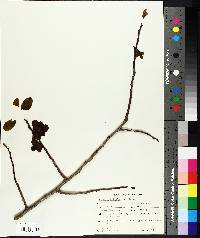

Asimina triloba

|

|

|

|

Family: Annonaceae

Common Pawpaw

[Annona triloba L., moreAsimina glabra Hort. ex K. Koch, Uvaria triloba (L.) Torr. & A. Gray] |

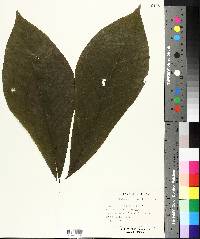

Shrubs or trees , 1.5-11(-14) m; trunks slender, to 20(-30) cm diam.; bark shallowly furrowed in larger trees. Branches spreading-ascending, slender; new shoots moderately to copiously brown-hairy apically, aging glabrous. Leaves: petiole 5-10 mm. Leaf blade oblong-obovate to oblanceolate, 15-30 cm, membranous, base narrowly cuneate, margins scarcely or not revolute, apex acute to acuminate; surfaces abaxially densely hairy, later sparsely so on veins, adaxially sparsely appressed-pubescent on veins, becoming glabrous. Inflorescences from previous year's shoots before or during new leaf emergence; peduncle nodding, (1-)1.5-2(-2.5) cm, densely hairy, hairs dark brown to red-brown; bracteoles 1-2, basal, usually ovate-triangular, rarely over 2-3 mm, hairy. Flowers maroon, fetid, 2-4(-5) cm diam.; sepals triangular-deltate, 8-12 mm, abaxially densely pilose; outer petals excurved, oblong-elliptic, 1.5-2.5 cm, abaxially puberulent on veins; inner petals elliptic, 1/3-1/2 length of outer petals, base saccate, apex recurved, surfaces abaxially glabrate, veins impressed adaxially, corrugate nectary zone distinct; pistils 3-7(-12). Berries yellow-green, 5-15 cm. Seeds brown to chestnut brown, 1.5-2.5 cm. Tree 6 - 9 m tall, trunk 8 - 15 cm in diameter Leaves: alternate, light green above, paler beneath, 10 - 30 cm long, 5 - 15 cm wide, inversely egg-shaped and tapering at both ends, non-toothed, covered with rusty hairs when young. Foliage smells like motor oil when crushed. Flowers: solitary, changing from green to brown to reddish purple, 3 - 4 cm wide, six-petaled with three petals much larger than the others. Fruit: is an elongated berry, greenish yellow changing to brownish black when ripe, 5 - 12 cm long, 2 - 6 cm in diameter. The poisonous seeds are shiny brown, 2 - 3 cm long, 1 - 1.5 cm wide, and flattened. Bark: smooth, dark brown with some gray to whitish patches and warty protrusions, developing scales and slight fissures with age. Twigs: green changing to brown, smooth or slightly hairy, releasing an unpleasant odor when broken. Terminal buds: 6 - 9 mm long, flattened, covered with dark brown, velvet-like hairs, lacking scales. Flower buds: nearly spherical, covered with two to three hairy scales. Similar species: Asimina triloba is easy to distinguish from other species in the Chicago Region due to its exotic appearance, very large leaves, irregularly elongated fruit, and velvety, naked terminal buds. Flowering: May Habitat and ecology: This species tends to form clonal colonies from root sprouts in the understory of mesic or wet woods. The Chicago Region is at the northern edge of this species' native range. Occurence in the Chicago region: native Notes: Asimina is one of two genera native to the U.S. in this mostly tropical plant family. Its somewhat exotic foliage, flowers and fruit give it a tropical appearance. Native Americans and early settlers widely used Asimina triloba. The bark contains the alkaloid analobine, which was used medicinally. The inner bark was used for stringing fish or woven into cloth. Etymology: Asimina is derived from its Native American name, arsimin, from which the French developed the word asiminine, which is an alkaloid found in the seed. Triloba is Latin for three-lobed, referring to the petals being arranged in sets of three. Author: The Morton Arboretum Usually shrubby, sometimes a tree to 10 m; young twigs hairy; lvs oblong-obovate, becoming 15-35 cm after anthesis, abruptly short-acuminate, gradually narrowed below; petiole 5-10 mm; fls from wood of the previous year, lurid purple, 3-4 cm wide, the sep 8-12 mm long, the outer pet 1.5-2.5 cm, broadly ovate, outcurved, the inner ovate, nearly erect, and nectariferous at the base; receptacle hemispheric or subglobose; peduncles hairy, (10-)15-20(-25) mm at anthesis; frs solitary or few, 6-15 נ3-4 cm, yellowish-brown, rounded at the tip; seeds flattened, 2-2.5 cm; 2n=18. Rich, damp woods; w. N.Y. and s. Ont. to s. Mich. and e. Nebr., s. to Fla. and Tex. Apr, May. Gleason, Henry A. & Cronquist, Arthur J. 1991. Manual of vascular plants of northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. lxxv + 910 pp. ©The New York Botanical Garden. All rights reserved. Used by permission. From Flora of Indiana (1940) by Charles C. Deam The papaw is probably found in every county of the state. It is usually local in the northwestern part and in the hills of the southern part. It prefers a moist, rich soil and is usually found in colonies on account of its habit of propagating by rootshoots. The fruit is edible and is relished by most people. It is desirable for ornamental planting and is free from insect pests and diseases. ...... Indiana Coefficient of Conservatism: C = 6 Wetland Indicator Status: FAC Diagnostic Traits: small tree forming patches via root sprouting; leaves large (15-30 cm), simple, alternate, their margins entire; buds naked; flowers dull purple, veiny, fruits 7-13 cm, fleshy, green, with several large seeds. Deam (1932): This species is also known as the yellow and white papaw. Recently some enthusiasts have christened it the "hoosier banana." There has been an attempt for years to cultivate the papaw, and some varieties have been named. The fruit is variable. The one with a white pulp is rather insipid and is not considered good to eat. The form with a yellow pulp is the kind that is regarded as the more palatable. The two forms are not botanically separated but Dean Stanley Coulter has made some observations on the two forms in the Ind. Geol. Rept. 24:145. 1899. He says: "Two forms, not separated botanically are associated in our area. They differ in time of flowering, in size, shape, color and flavor of the fruit, in leaf shape, venation, and odor and color of the bark. They are of constant popular recognition and probably separate species, never seeming to intergrade." It is desirable for ornmental planting on account of its interesting foliage, beautiful and unique flowers, and delicious fruit. It is very difficult to transplant a sucker plant, and in order to get a start of this species it is best to plant the seed or seedlings. It is usually found growing in the shade, but does well in full sunlight. The late Arthur W. Osborn of Spiceland, who has done much experimental work in propagating this species, reports some interesting cases of papaw poisoning. He says he knew a lady whose skin would be irritated by the presence of papaws. Some individuals after eating them develop a rash with intense itching. In one instance he fed a person, subject to the rash from eating the papaw, a peeled papaw with a spoon, and the subject never touched the papaw, and the results were the same. The American Genetic Association has taken up the subject of improving the fruit of this tree, and there is not doubt but that in the future this species will be of considerable economic importance. The tree is free from all insect enemies, and since it can be grown in waste places, there is no reason why it should not receive more attention than it does. |

|

|

|