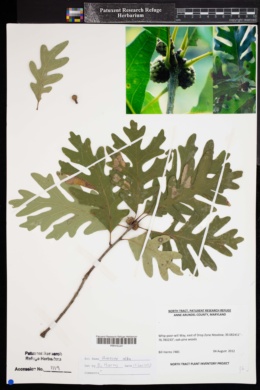

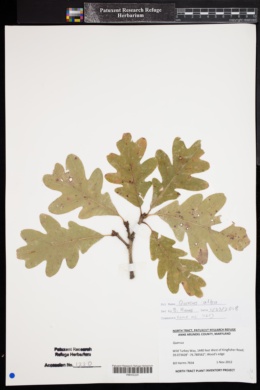

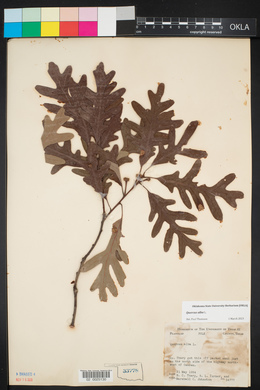

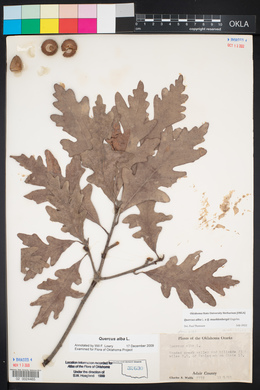

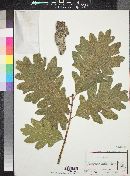

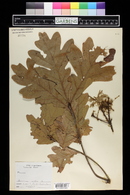

Quercus alba

|

|

|

|

Family: Fagaceae

Northern White Oak, more...white oak

[Quercus alba f. latiloba (Sarg.) E.J.Palmer & Steyerm., moreQuercus alba f. repanda (Michx.) Trel., Quercus alba var. latiloba , Quercus alba var. subcaerulea Pickens, Quercus alba var. subflavea Pickens] |

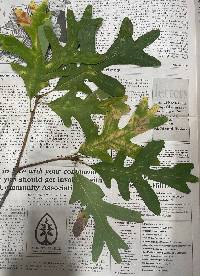

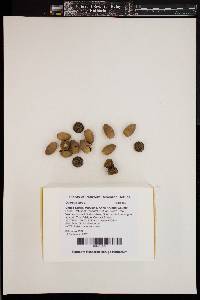

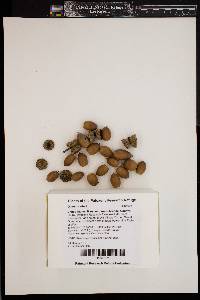

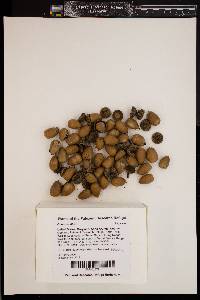

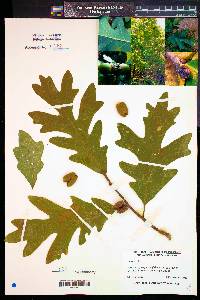

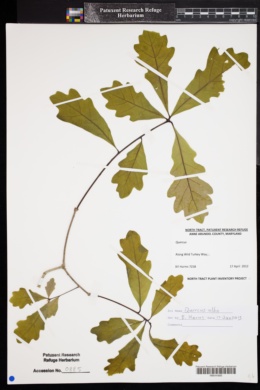

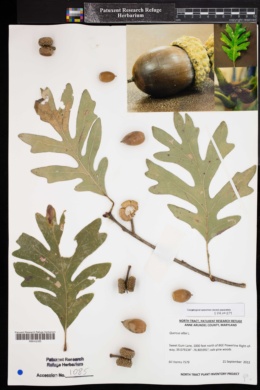

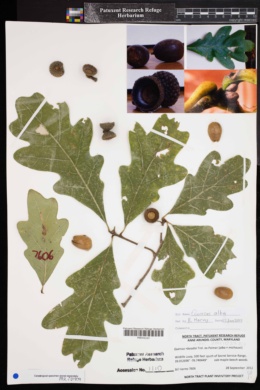

Trees , deciduous, to 25 m. Bark light gray, scaly. Twigs green or reddish, becoming gray, 2-3(-4) mm diam., initially pubescent, soon glabrous. Buds dark reddish brown, ovoid, ca. 3 mm, apex obtuse, glabrous. Leaves: petiole (4-)10-25(-30) mm. Leaf blade obovate to narrowly elliptic or narrowly obovate, (79-)120-180(-230) × (40-)70-110(-165) mm, base narrowly cuneate to acute, margins moderately to deeply lobed, lobes often narrow, rounded distally, sinuses extending 1/3-7/8 distance to midrib, secondary veins arched, divergent, (3-)5-7 on each side, apex broadly rounded or ovate; surfaces abaxially light green, with numerous whitish or reddish erect hairs, these quickly shed as leaf expands, adaxially light gray-green, dull or glossy. Acorns 1-3, subsessile or on peduncle to 25(-50) mm; cup hemispheric, enclosing 1/4 nut, scales closely appressed, finely grayish tomentose; nut light brown, ovoid-ellipsoid or oblong, (12-)15-21(-25) × 9-18 mm, glabrous. Cotyledons distinct. 2 n = 24. Flowering in spring. Moist to fairly dry, deciduous forests usually on deeper, well-drained loams, also on thin soils on dry upland slopes, sometimes on barrens; 0-1600 m; Ont., Que.; Ala., Ark., Conn., Del., Fla., Ga., Ill., Ind., Kans., Ky., La., Maine, Md., Mass., Mich., Minn., Miss., Mo., Nebr., N.H., N.J., N.Y., N.C., Ohio, Okla., Pa., R.I., S.C., Tenn., Tex., Vt., Va., W.Va., Wis. Considerable variation in depth of lobing occurs in the leaves of Quercus alba (M. J. Baranski 1975; J. W. Hardin 1975); the species is easily distinguished from others, however, by the light gray-green, glabrous mature leaves and cuneate leaf bases. In the past Quercus alba was considered to be the source of the finest and most durable oak lumber in America for furniture and shipbuilding. Now it has been replaced almost entirely in commerce by various species of eastern red oak (e.g., Q . rubra , Q . velutina , and Q . falcata ) that are more common and have faster growth and greater yields. These red oaks also lack tyloses and therefore are more suited to pressure treating with preservatives, even though they are less decay-resistant without treatment. Medicinally, Quercus alba was used by Native Americans to treat diarrhea, indigestion, chronic dysentery, mouth sores, chapped skin, asthma, milky urine, rheumatism, coughs, sore throat, consumption, bleeding piles, and muscle aches, as an antiseptic, and emetic, and a wash for chills and fevers, to bring up phlegm, as a witchcraft medicine, and as a psychological aid (D. E. Moerman 1986). Numerous hybrids between Quercus alba and other species of white oak have been reported, and some have been named. J. W. Hardin (1975) reviewed the hybrids of Quercus alba . Nothospecies names based on putative hybrids involving Q . alba include: Q . × beadlei Trelease (= Q . alba × prinus ), Q . × bebbiana Schneider (= Q . alba × macrocarpa ), Q . × bimundorum E. J. Palmer (= Q . alba × robur ), Q . × deami Trelease (= Q . alba × muhlenbergii ), Q . × faxoni Trelease (= Q . alba × prinoides ), Q . × jackiana Schneider (= Q . alba × bicolor ), and Q . × saulei Schneider (= Q . alba × montana ).

Tree 22 - 28 m tall, trunk 0.6 - 1.2 m in diameter Leaves: alternate, short-stalked, bright green above, pale green or with a waxy whitish coating beneath (glaucous), 12 - 20 cm long, 6 - 10 cm wide, with five to nine rounded lobes separated by depressions that are deep in sun leaves and shallow in shade leaves. Foliage turns brownish purple in fall. Flowers: either male or female, found on the same plant (monoecious). Male flowers are borne in hanging catkins, yellow, and 5 - 8 cm long, while the reddish female flowers are borne near leaf axils. Fruit: an acorn, developing in one season, solitary or in pairs, with a 0 - 2.5 cm long stalk. The deep saucer- or bowl-shaped cup covers one-quarter of the nut and has thick and warty scales with fine gray hairs. Nut light brown, 1.3 - 2 cm long and oblong to egg-shaped. Bark: light gray with shallow fissures or long, scaly blocks. Frequently, infection by a harmless fungus, <i>Aleurodiscus oakesii</i>, causes the non-living outer bark to fall off, leaving smooth, gray patches. Twigs: changing from bright green and hairy to reddish or light gray and smooth with age. Buds: dark reddish brown, 3 - 4 mm long, egg-shaped to almost spherical with a rounded tip. Each terminal bud is surrounded by a cluster of lateral buds. Form: open with wide-speading, gnarled branches. Similar species: Many oaks in the white oak group and Quercus robur have highly variable, similar leaves with rounded lobes. Quercus bicolor has round-toothed to shallowly lobed leaves that are whitish and hairy beneath, peeling bark on young branches, and a long-stalked acorn cup. Quercus lyrata has leaves that are inversely egg-shaped with irregular, rounded lobes, and an acorn cup that nearly covers the nut. Quercus macrocarpa has deeply lobed leaves that are inversely egg-shaped and hairy beneath, often corky-ridged twigs, and an acorn cup with long fringes along the margin. Quercus robur has very short-stalked leaves with ear-like lobes at the base, and a long-stalked acorn cup. Flowering: mid April to early June Habitat and ecology: Very common in oak-hickory forests and upland dry-mesic areas. Occurence in the Chicago region: native Notes: Quercus alba, the state tree of Illinois, is one of the most important lumber trees in the United States. Prior to the use of steel, its wood was used to build United States Navy ships. It is still used for furniture, cabinets, and flooring, however, some faster growing red oak species have replaced it. Quercus alba naturally hybridizes with Q. macrocarpa (Q. x bebbiana), Q. muhlenbergii (Q. x deamii), and Q. montana (Q. x saulei). Etymology: Quercus is the Latin name for oak. Alba comes from the Latin word for white. Author: The Morton Arboretum Tall tree with light gray, coarsely flaky, shallowly furrowed bark and widely spreading branches; twigs soon glabrescent; lvs obovate or oblong-obovate, cuneate at base, thinly floccose beneath at first (the pubescence can be rolled off with one's thumb), glabrous or nearly so at maturity, pale beneath, the lobes 3 or 4(5) pairs, ascending, oblong to ovate, rounded or rarely acute; acorns sessile or on pedicels to 4 cm, the cup deeply saucer-shaped, pubescent within, covering a fourth to a third of the nut; nut ovoid to cylindric-ovoid, 1.5-2.5 cm. Upland woods; Me. to Mich. and Minn., s. to n. Fla. and e. Tex. Extreme forms in which the lobes are scarcely more than large teeth may be distinguished from the chestnut-oaks by the lack of pubescence. Gleason, Henry A. & Cronquist, Arthur J. 1991. Manual of vascular plants of northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. lxxv + 910 pp. ©The New York Botanical Garden. All rights reserved. Used by permission. From Flora of Indiana (1940) by Charles C. Deam This species is found in every county of Indiana. Knowing this fact, I have not tried to preserve specimens from every county, but have tried to secure a series of the widely varying forms. The leaves vary greatly in their lobing, especially in the depth to which the blade is cut. We have some specimens in which the width of the blade between the lobes is only 5 mm. In others, the lobes are shallow and the uncut part of the blade is 30-40 mm wide. The lower surface of the blades is glaucous and entirely glabrous at maturity. My Starke County specimen, which is pubescent over nearly the entire lower surface, is an exception. The nuts vary from 10-30 mm long. It is found throughout the state except in low, wet grounds. I am including with the species the form latiloba with the blades cut less than half way to the midrib. This form is more abundant in the northern part of the range of the species. …… Indiana Coefficient of Conservatism: C = 5 Wetland Indicator Status: FACU Deam (1932): Wood heavy, hard, close-grained, tough, strong, and durable. On account of its abundance and the wide range of uses, it has always been the most important timber tree of Indiana. Formerly the woods were full of white oak 1-1.5 m (3-5 ft) in diameter, but today trees of 1 m diameter with long straight trunks are rare indeed. Michaux, who traveled extensively in America, 1801-1807, while the Mississippi Valley was yet a wilderness, remarks: "The white oak is the most valuable tree in America." He observed the ruthless destruction of this valuable tree and predicted that the supply would soon be depleted, and that America would be sorry that regulations were not adopted to conserve the supply of this valuable tree. Michaux's prediction has come true, and yet no constructive measures have been provided to insure the Nation an adequate supply of this timber. It should be remembered that it requires two to three hundred years to grow a white oak a meter in diameter, and if we are to have white oak of that size in the next generation the largest of our present stand must be spared for that harvest. White oak was formerly much used in coonstruction work, but it has become so costly that cheaper woods take its place. At present it is used principally in cooperage, interior finish, wagon and car stock, furniture, agricultural implements, crossties, and veneer. Indiana has a reputation of furnishing the best grade of white oak in the world. Little attention has been given this valuable species in horticultural or forestal planting. This no doubt is due in a great measure to the slow growth of the tree. It should be used more for shade tree, ornamental, and roadside tree planting. There are good reasons why white oak should be much used in reforestation. For this purpose one or two-year-old seedlings or seed may be used. If seed are planted the nuts may be stratified or planted direct to the place where the trees are desired to grow as soon as they fall or are mature. The nuts should no be permitted to lie on the ground too long before they are gathered because they dry out or sprout. The best results will be obtained if the nuts are planted with the small end down, and covered about an inch deep with earth. If the ground is a hard clay soil and the small end of the nut is placed down a half inch of earth on the nut is sufficient. Rodents often destroy the nuts, and if this danger is apprehended it is best to poison the rodents or to stratify the seed, or grow seedlings and plant when they are one or two years old. In foretal planting it is suggested that the planting be 4 x 4 to 6 x 6 feet. |

|

|

|