|

|

|

|

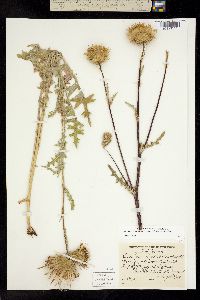

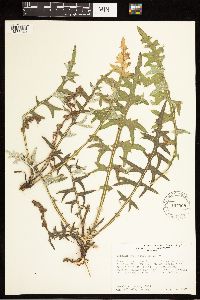

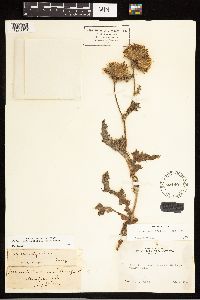

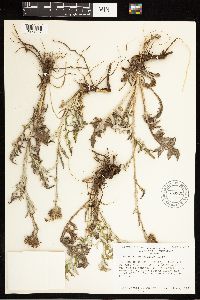

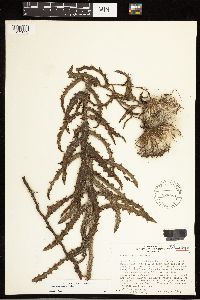

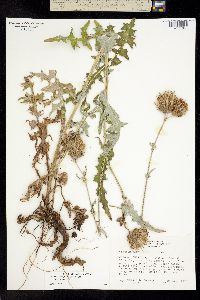

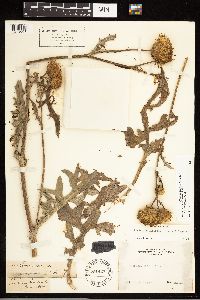

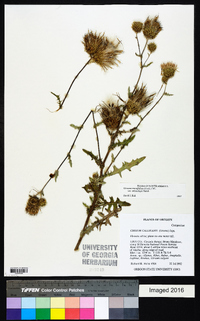

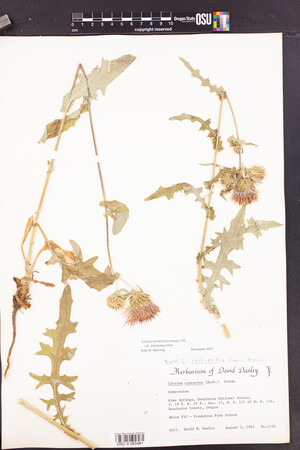

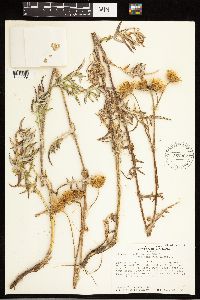

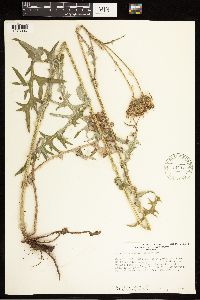

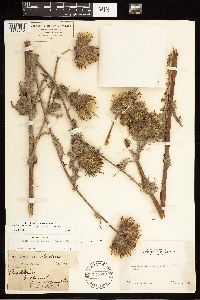

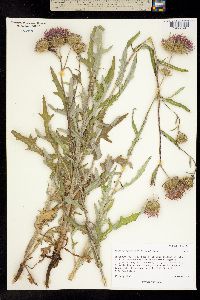

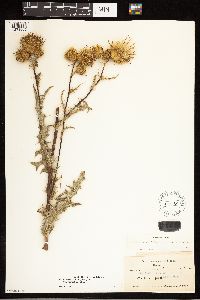

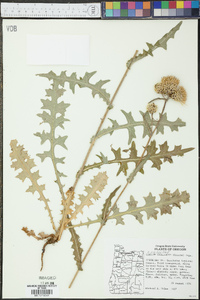

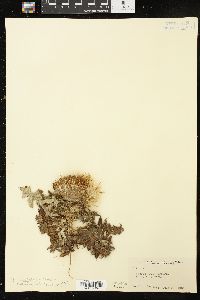

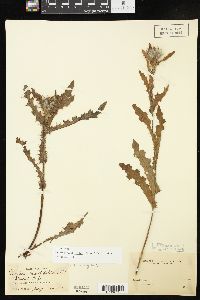

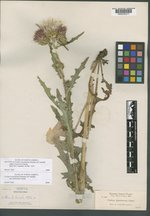

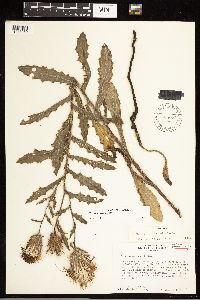

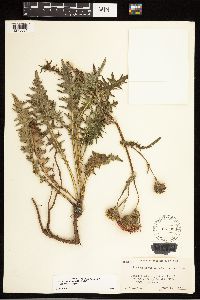

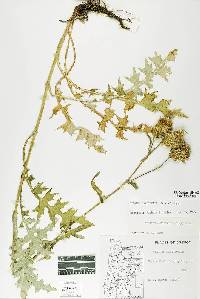

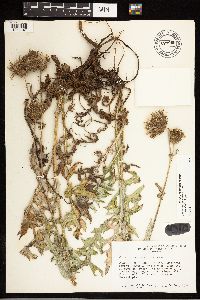

Family: Asteraceae

Few-Leaf Thistle

[Cirsium acanthodontum S.F.Blake, moreCirsium amblylepis Petr., Cirsium callilepis , Cirsium callilepis var. oregonense (Petr.) J.T.Howell, Cirsium callilepis var. pseudocarlinoides (Petr.) J.T.Howell, Cirsium mendocinum Petr., Cirsium oreganum Piper, Cirsium remotifolium subsp. oregonense Petr., Cirsium remotifolium subsp. pseudocarlinoides Petr., Cirsium remotifolium subsp. remotifolium , Cirsium stenolepidum Nutt., Cnicus remotifolius A. Gray] |

Perennials, 20-150 cm. monocarpic; taprooted or polycarpic, perennating by runner roots. Stems usually 1, erect, finely arachnoid-tomentose, sometimes villous with septate trichomes below nodes; branches 0-10+, slender, usually arising in distal 1/2, ascending. Leaves: blades linear-oblong to oblanceolate or elliptic, 7-30 × 1-15 cm, unlobed and spinulose to dentate or shallowly to deeply pinnatifid, lobes well separated, linear to triangular-ovate, dentate to deeply lobed, main spines 2-5 mm, slender, abaxial faces green to gray, thinly to densely arachnoid-tomentose, sometimes glabrate, sometimes villous with septate trichomes along veins, adaxial green, glabrous; basal sometimes present at flowering, sessile or winged-petiolate; principal cauline mostly in proximal 1/2, winged-petiolate or sessile, bases narrowed, sometimes auriculate; distal well separated, progressively reduced, becoming bractlike, often unlobed or less deeply divided than the proximal, sometimes spinier than proximal, bases often distally expanded and auriculate-clasping. Heads few-many, borne singly or in openly branched in corymbiform, racemiform, or paniculiform arrays on main stem and branches, sometimes also in distal axils, not closely subtended by clustered leaf bracts. Peduncles (0-)2-15 cm. Involucres ovoid to hemispheric or campanulate, 1.5-2.5 × 1.5-3.5 cm, glabrous to arachnoid-floccose. Phyllaries in 6-8 series, subequal to strongly imbricate, green, linear to obovate (outer) to linear (inner), abaxial faces with inconspicuous glutinous ridge; outer and middle bases appressed, margins entire to spinulose-dentate or broad, scarious, lacerate-dentate, spines absent or ascending to spreading, 1-2 mm; apices of inner sometimes flexuous or reflexed, narrow, flat, entire or expanded, scarious, and lacerate-dentate. Corollas creamy white to purple, 18-28 mm, tubes 7-12 mm, throats 5-12 mm, lobes 3.5-7 mm, style tips 4-6 mm. Cypselae tan to dark brown, 4.5-5.5 mm, apical collars differentiated or not; pappi 13-23 mm. 2n = 32. Cirsium remotifolium occurs from the Coast Ranges and valleys of the Pacific Northwest to the western slopes of the Cascade and Klamath ranges, south in the California North Coast Ranges to the San Francisco Bay region. It is closely related to the C. clavatum complex of the Rocky Mountains region. Both have a similar growth habit and some forms variably express the character of broadly scarious, lacerate-toothed phyllary margins. Gray, in naming Cnicus carlinoides var. americanus, included as syntypes both California and Colorado specimens. F. Petrak (1917) treated both the West Coast plants and those of the Rocky Mountains as Cirsium subsect. Americana, recognizing C. remotifolium with several infraspecific taxa plus two other species, C. callilepis and C. amblylepis from the West Coast, and four additional species from the Rocky Mountains. A. Cronquist (1955) rejected Petrak´s subspecies, treating C. remotifolium in a restricted sense, limited to plants of Washington and Oregon without dilated phyllary tips, and circumscribed C. centaureae broadly to include the Rocky Mountains and West Coast plants with dilated phyllary tips. Because of the frequent presence of dilated phyllary tips in C. remotifolium in the restricted sense, Cronquist acknowledged the likelihood of past introgression with C. centaureae in the broad sense. J. T. Howell (1960b) recognized three species: Cirsium remotifolium, C. acanthodontum, and C. callilepis, the latter with four varieties collectively corresponding to the West Coast representatives of C. centaureae (in the sense of Cronquist). Because of the great similarity of the various West Coast plants and their intergradation, I see no value in recognizing two or more species. The West Coast and Rocky Mountains plants are clearly related, but are separated by the Great Basin region and there is little chance of current genetic interchange. As is often the case with American Cirsium, genetic enrichment from past hybridization with other nearby species within their respective areas has likely been fertile ground for evolutionary diversification. Different species have contributed genes in the Pacific states and in the Rockies. I have chosen to recognize two geographically-based species complexes, each with intergrading races here treated as varieties. I treat the West Coast plants as C. r |